Abstract - Father Sky

Native American communities are tied to the land historically, physically, culturally, and spiritually. Communities were forcibly removed from traditional homelands either by settlers taking over Native American lands or by government designation, leading to relocation to spaces that were constitutionally designed as unmarketable for thriving economic enterprise. Without the ability to capitalize a strong government from the land like other communities, to bring in outside businesses within the community to circulate local dollars, and to build generational wealth and knowledge of a foreign financial system, Native American individuals and families have been stripped of the American dream of cultivating wealth in the United States.

Prayer, Song, and Introduction - East/Sweetgrass/Beginning

“Gmmigwechiwendaamin omaa mawadishiweyang noongom miinawaa bagosendamang wii nagadawendamang weweni.

We are thankful to be here gathering today and we hope to consider things carefully in a good way.”

(Anishinaabemowin/English)

“Nimiigwechwendam maabaa bimaadiziiwin” 1

I am in a state of gratitude for this life.

Gizhe-Manidoo,

Creator,

I want to take a moment to acknowledge my gratitude for the collective knowledge shared for this series of articles: for the knowledge shared from ancestors answering questions through dreams and prayers, for my brothers and sisters with lived experiences and sharing their cultivated knowledge, and for my western teachers imparting the “western ways” of knowing and communicating in this world. I also want to thank the National Endowment for Financial Education for their consideration of hosting these articles and sharing this story.

Chii Miigwetch,

Many Thanks

This is the first piece in a seven-part series unpacking the complexities surrounding financial education for Native American communities, utilizing interviews from prominent Native American individuals across the financial education sector and accessible literature. Together, these seven pieces will create a snapshot of this landscape. As financial knowledge coexists with access to financial products and services in the National Endowment for Financial Education’s Personal Finance Ecosystem, this article discusses the history of land-based asset allocation for Native communities, and its relationship to asset-building and wealth generation within the United States. A thriving economy is imperative to the implementation and sustainability of financial education. “You cannot ‘financial education’ your way out of poverty,” states Native Community Development Financial Institution Four Bands Community Fund Executive Director, Lakota Vogel, Cheyenne River Sioux, sharing the collective frustration that many Native American practitioners face in uplifting community members from systemic poverty. Financial education, defined by the National Endowment for Financial Education as a systematic approach to cultivating financial knowledge and decision-making skills, is an integral part of the United States economic system. However, it cannot be discussed without addressing several intersections with current native American lived experiences.

History - South/Cedar/Growth

Before colonization, thousands of Native American communities operated intricate economies, creating vast trade routes across the Americas, developing natural currencies, and engaging in exporting goods. Once colonization began in the mid-1400s, Native American communities endured a series of events that would strip nations of their ability to cultivate the land for sustaining a subsistence-based economy, let alone basic needs for survival. The lasting effects of this process have left these communities with strong cultural ties to ancestral lands economically barren and bound to federal regulations that jeopardize sovereignty at the cost of cultivating economic strength.

“The American Indian is of the soil, whether it be the region of forests, plains, pueblos, or mesas. He fits into the landscape, for the hand that fashioned the continent also fashioned the man for his surroundings. He once grew as naturally as the wild sunflowers, he belongs just as the buffalo belonged…”

– Luther Standing Bear, Oglala Sioux Chief

A subsistence economy is one that is reliant upon the renewable use of wildlife resources for personal and community consumption and goods. “Subsistence is the mainstay of food security in Native villages. Subsistence contributes to the cultural and physical survival of Native communities on a daily basis,” states Dr. Rosita Worl, Tlingit, chair of the Subsistence Committee at the Alaska Federation of Natives. In addition, Native American culture and society relies on the importance of an economy based on the collective strength, rather than the western model of individual wealth accumulation, sustainably harvesting and growing natural resources. It is important to understand the distinction between these two models of economic management because the indigenous model is a holistic approach that encompasses respect and reciprocity with natural surroundings and the collective community. Native American tradition and values conflict with the western economic model.

“Despite each individual Native American Nation being very different in terms of beliefs, language and culture, there is one thing at the center of most American Indian spiritual belief systems and that is the basic principle that spirituality draws heavily upon the lands and beings of our sacred Grandmother Earth,” according to the Red Road Project. Native culture is rooted in the land and the bounty of life that it brings forth. And naturally, the economic systems of Native American communities are also tied to the land.

According to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, “A federal Indian reservation is an area of land reserved for a tribe or tribes under treaty or other agreement with the United States, executive order, or federal statute or administrative action as permanent tribal homelands, and where the federal government holds title to the land in trust on behalf of the tribe… There are approximately 326 Indian land areas in the U.S. administered as federal Indian reservations (e.g., reservations, pueblos, rancherias, missions, villages, communities, etc.).”2

The signing of The Indian Removal Act in 1830 by President Andrew Jackson forcibly moved Native Americans from their home territories to U.S. Government-designated lands, the most famous being “The Trail of Tears.” However, several relocation marches took place removing about 100,000 Native Americans from their homelands throughout the 1800s. As stated by the National Congress of American Indians, “Most tribal lands will not readily support economic development.3 Many reservations are located far away from the tribe’s historical, cultural, and sacred areas, as well as from traditional hunting, fishing, and gathering areas.” Moreover, The Homestead Act of 1862 distributed around 48 million acres of Native American land to settlers.

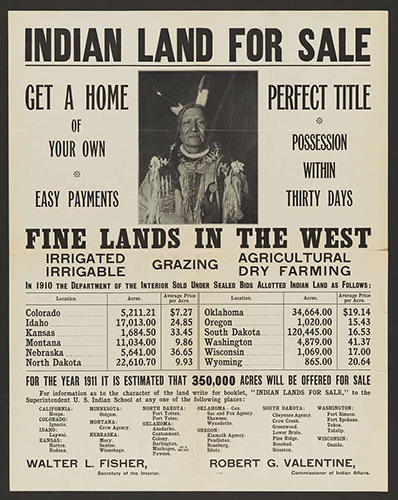

In 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Indian Appropriations Act stating, “No Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power within whom the United States may contract by treaty.” This eliminated individual treaties with tribal nations. In 1887, the Dawes Severalty Act was implemented to break apart the reservation lands by granting allotments to individual Native Americans. Consequently, much of this land was checkerboarded with non-Native owned land, sold off to non-Natives, and fractionated through the division of land to heirs.

Fifty years later, in 1934, the Indian Reorganization Act solidified the privatization of Native reservation lands; terminating the allotment system of land, tribes could self-govern and incorporate businesses, and a $10 million revolving loan fund was made available through the Bureau of Indian Affairs for commercial endeavors. As outlined by the U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resources and Revenue Data, “Native American land ownership is complex.” There are two types of Native land (trust land, where the government holds the legal title) and fee land (land purchased by tribes.)

Discussion - West/Tobacco/Maintenance

Manifest Destiny is the philosophy that expansion westward was a duty for white Americans to settle the continent through conquering the land.4 This process of expansion was at the expense and devastation of Native people and culture. Since Native culture and survival are tied so closely with generational knowledge of traditional lands, settlers and the U.S. government were invoking mass genocide by removing Native Americans from ancestral, with an estimated 50 million American indigenous lives lost.

The Native Americans that remain were left on lands that were not their ancestral territories or small, insufficient portions of their historic lands (now known as reservations).

John Gast, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

“Reservation lands mostly are, what we call in federal Indian law, restricted lands, meaning they probably can't be sold or alienated or collateralized without the consent of the federal government or of the tribe or both, and that creates some serious bureaucratic hurdles to developing and using financing to start governmental projects or economic development projects,”5 states Professor Matthew L.M. Fletcher (Anishinaabe), Harry Burns Hutchins Collegiate Professor of Law and Professor of American Culture at the University of Michigan. He also noted that due to the perceived jurisdictional complexities and implicit racial biases, lenders are hesitant to work with Native tribes.

“We hang on to, we cherish trust land, even though it has incredible negative economic benefits because it's our only way to maintain solid jurisdictional power,” said Lance Morgan (Ho-Chunk), president and chief executive officer of Ho-Chunk, Inc., clarifying the role of trust lands for Native Americans.

“We're in a competitive jurisdiction with the states and we will trade jurisdictional power for economic power any day of the week. That's unique to our identity, but I don't think tribes should have to choose tribal sovereignty and poverty as one.”6

In examining economies in their most basic layers, the complexities of sovereignty of land and barriers to economic development become more defined. First Nations Development Institute and Oweesta Corporation’s Native-specific financial education curricula, “Building Native Communities,” teach the concept of an economy with multiple layers, starting with individual, extending toward community, and concluding with non-community.

The “individual layer” of an economy is made up of the individually-owned small businesses, where owners are within the community and invest and circulate revenue back within the community.

The “community layer” consists of small businesses, nonprofit organizations, and tribally-owned enterprises that will also be circulating revenue back into the community. A large misconception of tribal enterprises, especially casino revenue, is that revenue from these businesses act like a for-profit entity and the CEO and board members are profiting or in large payments to tribal citizens. However, the business revenue supports the government and social programs (e.g., housing and healthcare) offered to the community and tribal citizens, unlike other businesses or corporations in the non-Native world. Professor Fletcher reflected on interactions with other governments and lending entities, highlighting how tribal nations operate just as independent governments in serving their respective community members: “That's the only reason that tribes exist. I mean, there's cultural aspects to this of course, but that's what tribal governments are supposed to be doing.”7

In addition to serving their own respective sovereign governments, certain states also mandate a percentage of gaming revenue from tribes to be allocated to the cities, towns or counties for public services. For example, the Pascua Yaqui Tribe takes 12% of its total annual contribution to the surrounding communities in their Gaming Revenue Sharing Funds Program. To further understand the breadth of tribal enterprise and their importance in economic development in Native communities, the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Center for Indian Country Development built and examined a dataset of nearly 1,200 tribally-owned small businesses in 2021 and states, “Tribally-owned businesses create economic opportunity for Native Americans and non-Natives alike. With the challenges tribal nations face in generating revenues, tribes create these enterprises as a key revenue stream to support tribal governments and therefore provide essential public goods to tribal communities.”

The “non-community layer” consists of businesses that do not have the opportunity to infuse capital back into the community. Because of trust land, there are very few non-tribal businesses owned and operated on reservations, including banking institutions. According to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s 2019 survey, 16.3% of Native communities had unbanked households, compared to Black (13.5%), Hispanic (12.2%) and White (2.5%).

“A lot of Indians are underbanked,” Professor Fletcher, Anishinaabe, explains, “it is my understanding, that if they live on the reservation, they probably are in a banking desert, and it's a really difficult thing for tribal members to live and breathe, so to speak, in the financial sector, in the financial space, if they live in Indian country. It's not impossible, but it is really difficult.”

He also shared a personal experience in a vast financial desert on the Hoopa Valley Tribal Reservation where the closest bank was over 90 minutes away. Not only was there an extremely long distance to conduct in-person banking, but this specific bank was also the only one available and not the best banking option in terms of products and services available.

In the article, “Tribal Leakage: How the Curse of Trust Land Impedes Tribal Economic Self-Sustainability,” the authors articulate the difficulties entrepreneurs face on lands held in trust, as they are not able to borrow against the equity in their homes or land. With fewer small businesses on reservation lands, consumers are forced to purchase goods and services outside of their communities, resulting in an economic leak. Lance Morgan describes the average reservation as a government entity sharing a jurisdiction with a state entity, creating conflicting government entities fighting over the same jurisdiction. Outlined in his paper, “Ending the curse of trust,” he explains why poverty is perpetuated on tribal trust lands. Where its original intent was to keep non-tribal members from stealing the little land that was left to the respective tribes, it has created an economic desert where the tribe cannot utilize the lands for bonds to build schools or roads.

Morgan also noted that farming is recent for Native communities because of new, non-collateralized access to farm capital. “If you look at ranching, most Native ranch land is ranched by Natives because you can collateralize the animals. For a large swath of the country, Native American farming has been wiped out, especially on the individual basis,” he states. “So, all you can do is lease out your land to a farmer who then makes money off of it, or you lease out your energy resources to an energy company who makes money off it. And the fact that all this makes us poor over time.” 8

At the Ho-Chunk Tribe of Nebraska, they are farming 6,000 acres, but had to utilize corporate credit to do so. In addition, they had left farmland out of trust to leverage it to purchase more land. If it had been put into trust, the tribe would not be able to leverage it the same.9

“So when we're thinking about assets, we're including a wide range of assets, everything from tribal sovereignty, natural resources, spirituality, important assets such as homes, education, tribal lands,” states Dr. Christy Finsel, Osage, executive director of the Oklahoma Native Asset Coalition. “In terms of Native lands, homelands, territories, reservations, and thinking about how do we protect our Native lands and engage in development with a Western financial system in a way that is sustainable and can help us continue to build assets in a broad way.” 10

In addition to supporting individual and community-based economies, tribal nations can expand beyond the government-set reservation borders to participate in the financial systems. Professor Fletcher and Lance Morgan noted that tribal economic operations are not required to be held on trust land. “‘All the money that you get for the rest of history is going to come exclusively from this plot of land.’ That's bullshit. We don't have to, and we've bought in to it by thinking we have to only do things on our reservation lands,” states Professor Fletcher. “And yes, it’s true… the gaming act says we have to do that, but there’s not a lot of laws that require us to operate from a home base. So, I think that that’s a philosophical understanding that should change.”

Wisdom - North/Sage/Conclusion

In conclusion, through a process of Manifest Destiny and land relocation, Native Americans have been stripped of the ancestral lands and ways of knowing the land to cultivate the traditionally thriving subsistence economy. Moreover, the restrictions on Native American lands have a negative snowball effect on economic growth and asset acquisition for Native Americans. The inability to collateralize land as a tool to leverage additional assets at an individual and governmental level make it impossible to build and sustain small businesses on reservation lands, which in turn cause an economic leak to external businesses that do not support the tribal community economy. The fewer financial enterprises and diminished economic opportunity means that there are higher rates of unemployment, lower rates of generational wealth and knowledge transference, and lower overall financial wellbeing. Without the initial assets to manage, financial education cannot be fully applied. Tribal communities could provide the best financial knowledge, but without the assets to manage, it proves useless. Financial knowledge is a core concept in the National Endowment for Financial Education’s Personal Finance Ecosystem, interwoven with Financial skills and Access and Inclusion. You cannot “financial education” your way out of poverty, and it is extremely difficult to climb out of poverty living in an economic desert.

Disclaimer - Mother Earth

There are 574 federally-recognized tribes and hundreds of unrecognized tribes in the United States, each with a unique colonization story that has influenced their community members’ and descendants’ interactions with the mainstream financial system. These articles are intended to explain a generalized Native experience and support a journey of positive change in relation to Native American, Hawaiian Native, and Alaskan Native communities

About the Weaver - The Spirit Within

Boozhoo, Migizi ‘ikwe Nindigoo. Stephanie Cote Nindizhinikaaz. Grand Traverse Band Odawa minwaa Ojibwe Nindibendaagoz. Maengun Nidodem.

Hello, spirits know me as Eagle woman. I am called Stephanie Cote. I am from the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians. I am from the Wolf clan.

Stephanie Cote descends from a lineage of basket weavers. Honoring her ancestry, these articles are woven from common Native knowledge, accessible online articles, and the wisdom imparted by Native peers and elders to support hypotheses developed from the intersectionality of Native American experience and financial education. She is Odawa and Potawatomi from the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians from Northern Michigan and a senior program officer at Oweesta Corporation leading the Financial Education and Asset Building Department.

1 https://ojibwe.net/songs/traditional/nimiigwechwendam/,

2 https://www.bia.gov/faqs/what-federal-indian-reservation,

3 https://www.ncai.org/policy-issues/land-natural-resources/trust-land,

4 https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history/the-early-republic/age-of-jackson/a/manifest-destiny,

5 Interview with Professor Matthew Fletcher; Date May 11, 2023,

6 Interview with Lance Morgan; Date May 24, 2023,

7 Interview with Professor Matthew Fletcher; Date May 11, 2023,

8 Interview with Lance Morgan; Date May 24, 2023,

9 Interview with Lance Morgan; Date May 24, 2023,

10 Interview with Dr. Christy Finsel; Date May 31, 2023