Abstract- Father Sky

Building upon the series examining the intersection of Native American experience in the United States and financial education, this article addresses current barriers to accessing mainstream financial institutions, equitable capital, and relevant financial education. This article discusses contemporary data regarding Native American-specific access issues and a few efforts to address these matters.

Prayer, Song, and Introduction- East/Sweetgrass/Beginning

Anishnaabe Prayers

(Anishinaabe/English)

“Miigwetch Gzhemanido

Thank you Creator

Gii-miizhiyaang nbiish maanpii Akiin

The gift of water on Earth

Wii bmaadzimgaad kin

Feed

Akin aa zaagkiimgod, wesiinyag miinwaa Bemaadzidjig

the plants, the animals and the people

Gitchi Miigwetchi goo Gzheminidoo

Great thanks to you Creator

Niibwaakaawin miinwaa

For your wisdom and

Kina gegoo gaa-zhitooyin

your gifts”

Maanda Giizhiigak (This Day)

“Yaaa way yaa weyo weyo weyo

Yaaa way yaa weyo weyo weyoooo

Mii noongwa maanda maadseg

This day that starts

Wey weya hey wey weyo

Noongwa maanda giizhiigak maamwidooying

This is the day that we all come together

Weya heyo

Weya wey haa wey

Weya weya ho aweyo weya heyo”

Gitchi-manadoo, Creator, thank you for this opportunity to share our Native American past and present experiences. May this series uplift voices unheard, bring light to that which is cast in the shadows, clear vision to those that cannot see the truth, and create change for a life with just practices for seven generations into the future. Chii Miigwetch, Many Thanks

This is one piece of a seven-part series unpacking the complexities surrounding financial education, including financial well-being, for Native American communities, utilizing interviews from prominent Native American individuals across the financial education sector and accessible literature. Together, these seven pieces create a snapshot of this landscape.

A Core Concept in the National Endowment for Financial Education’s (NEFE’s) Personal Finance Ecosystem is “Financial Knowledge and Access,” defined as, “the individual’s ability to act in their own self-defined, best financial interest. It is comprised of two key elements: the financial knowledge and skills (i.e., financial literacy) to decide or act and the opportunity to take action and exercise choice within financial society (i.e., access and inclusion).” In this model, access and inclusion refers to “participation in financial society, which NEFE defines as the opportunity and awareness to take action and exercise choice within financial markets, the financial services industry, and all aspects of financial life.”

History- South/Cedar/Growth

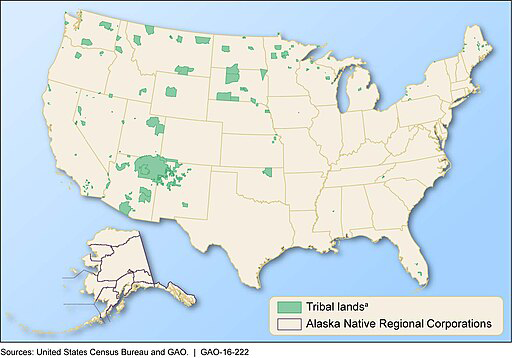

In the 2019 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s “How America Banks: Household Use of Banking and Financial Services” survey, 16.3% of American Indian identified individuals were unbanked, compared to 13.8% Black, 12.2% Hispanic, 2.5% White and 1.7% Asian. The survey also found that American Indian individuals were more likely to use check-cashing services and money orders than other ethnicities. The 2017 Native Nations Institute study “Access to Capital and Credit in Native Communities: A Data Review,” shows that for tribes in the contiguous United States, the average distance to the nearest physical banking branch or ATM was 12.2 miles, with some tribes being over 70 miles away.

In addition to the physical access barriers, Native Americans are continuously victims of redlining from mortgage lenders, broken promises and treaties from the United States government and targets for predatory lending. The 2023 NEFE public opinion poll “Experience of Discrimination and Financial Well-being in Native Communities” found that 33% of respondents had reported experiencing bias, discrimination or exclusion by of from institutions and individuals within the financial services sector and 40% of respondents living within 50 miles of a Native American reservation, Hawaiian homestead, or Native Alaska village had experienced bias, discrimination, or exclusion in seeking financial services. In this poll, 17% of respondents were unbanked, which is similar to the 16.3% in the 2019 FDIC findings. The poll also unveiled that 30% of respondents had used check-cashing services, 20% had used a money transfer service, and 10% had taken out a payday or payday advance loan, within the past 12 months.

The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), enacted by Congress in 1977, “is intended to encourage depository institutions to help meet the credit needs of the communities in which they operate.” Institutions insured FDIC are also regulated by it, as well as the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The CRA does not require banks to offer credit that will jeopardize their financial stability and are evaluated on the services provided to low- and moderate-income communities and individuals within the areas which they serve. Assessment areas “must consist of whole census tracts; must include bank’s main office, branches, and deposit-taking ATMs; and must include where the bank has originated or purchased a substantial portion of its loans.” Unfortunately, because Native American communities are predominately banking deserts, they are also considered CRA deserts and out of the service area for most banking institutions. On October 24, 2023, new rules around Native Land Areas (NLAs) were introduced to the reformed objectives of the CRA. Technically, CRA activities taking place on the NLAs would have qualified under the prior rule. However, the new reform clarifies these geographic locations specifically. “The definition focuses on lands and communities that, as noted by commenters, have generally experienced little or no benefits from bank access or investments,” states the Federal Reserve of Minneapolis Center for Indian Country Development. This new rule expands capital opportunities for CRA funding to reach beyond the service area boarders of the current banking locations as long as qualifying activities are limited to “community revitalization or stabilization activities, essential community facilities and essential community infrastructure, and disaster preparedness and weather-resiliency activities,” as opposed to direct financial services or capital to individuals.

In an effort to create accessible financial services, there are 30 Native American-owned banks or credit unions, defined as the majority of voting owners or bank board members are Native American, serving Native American communities across the United States. There is also a “Get Banked Indian Country” program through Oklahoma Native Assets Coalition (ONAC) that partners with financial institutions in joining the national Bank On program. These account features include: low fees and no hidden fees, a checking or checkless checking account with no-fee debit or prepaid cards, $0-$25 required to open the account, and free direct deposit and bill pay services. “Get Banked Indian Country hopes to increase the number of Native-owned and Native-serving financial institutions that offer FDIC insured Bank On certified accounts.”

With fintech on the rise, fair and equitable financial services are now more accessible, however, the physical remote locations of Native American communities place them at risk for broadband access issues. As described in the article “The Origin Story: Manifest Destiny’s Creation of Economic Deserts and the Devastation of Subsistence Economy,” Native Americans were placed in very remote locations throughout the United States, creating economic, food, and broadband deserts. In the 2019 Federal Communications Commission study, 99% of the U.S. urban population had access to broadband internet while only 65% of American Indian rural units had access to the same quality internet. In addition, the data indicates that 73.3% of non-Native rural areas are covered by a terrestrial fixed broadband provider, where only 46.6% of rural American Indian communities have fixed coverage. The issue goes beyond the ability to access broadband. Many companies have control over the price and quality of internet provided to these communities.

Discussion- West/Tobacco/Maintenance

Historically, Native American communities have been left out of mainstream financial systems. “Proximity to traditional funding sources, having representation from the traditional funding sources being present and available in the communities is something that is lacking,” states Christopher Cote (Anishinaabe), business development impact manager at First American Capital Corporation. In working at a Native Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) serving the entire state of Wisconsin, one of the largest barriers is lack of knowledge of the resources available. A hurdle he sees for financial institutions is, “building a relationship with the community, taking a leap of faith and becoming a part of that community and providing benefit to that community, so they can trust the banking institution.” (interview, July 13, 2023) Several interviewees noted that historical injustices around financial institutions have led to a lack of trust within the modern banking systems. Chantay Moore (Dine), CFEd, MBA and director of Native American Financial Literacy Services, expresses that the urban experience with accessing the financial mainstream is tied into marketing. Building that trust is difficult when the demographic is not represented. She shared a story about an insurance company that chose to use Native imagery and that it was easier to share this company with Native clientele with this simple change in marketing. “I even felt more empowered as a financial professional to just even market or talk about that particular company just because of that brochure,” Moore said.

In addition to physical accessibility, Dr. Vanessa Esquivido (Nor Rel Muk Wintu, Hupa, Xicana) points out that accessing the language of the financial system is similar to the ways that laws are written. “They’re written in a specific way for us not to understand them and you need to have a law degree to understand the law language around it,” she emphasizes. “It’s the same way around the western financial systems in that the vocabulary is inaccessible to a lot of people… Capitalistic society wants to keep that one percent in the highest regard, and they know how to move around that system,”(interview, July 19, 2023). For Dawn LeBeau (Lakota), education around financial services and the terminology is a large barrier for Native community members. They are affected by internet services and classroom accessibility. She notes that without the correct tools and resources, such as the specific language used in finances, community members are not able to navigate building businesses, opening Individual Development Account savings programs, or know to save for the downpayment of their first vehicle (interview, July 14, 2023).

Professor Matthew Fletcher (Anishinaabe), Harry Burns Hutchins Collegiate professor of Law and professor of American Culture at the University of Michigan, notes the misconception that financial institutions have about working with Native American communities and tribal law. “A big part is that the financial sector doesn’t want to deal with Indian Country because it is too hard.” He states that the misconceptions of working with indigenous populations are “rooted in a lack of education about Indian people.” (interview, May 11, 2023) Because of this lack of cultural competency, many Native community members face substantial hurdles when accessing capital. “I think as we as native people are having higher levels of just having to jump through more hoops to demonstrate who we are and that we're capable of maintaining a mortgage. That's why they have loan guarantees, because we as Native people are still not trusted to really know what it is to manage our money or to be able to understand the Western world and the financial system when it's not truly necessary on so many levels,” shares Onna LeBeau (Omaha), director of the Office of Indian Economic Development. “But that's what's placed upon our people. And so, I think it's harder for our people because they know going in that they already have a strike against them.” (interview, May 15, 2023) It is the lack of knowledge about operating financial enterprises in and around tribal communities that causes Lance Morgan (Ho-Chunk), president and CEO of Ho-Chunk Incorporated, to believe the main barrier is the inability to leverage trust land as an asset, as well as the financial sector’s inability to understand working with folks living on trust lands. He goes on to explain that this has created a handicap for economic growth and development, and that tribes have had to create economic systems that work within the current laws governing the tribe and land themselves. “If you can get enough capital, you can get beyond it. But the underlying structure that has impoverished us for 150 years is still sitting right there.” (interview, May 24, 2023)

In addition to educating financial institutions on Native American culture and shedding light on perpetuated misconceptions of modern Native finances, Lanalle Smith (Dine), senior program officer of Oweesta Corporation shares that there needs to be a vision created by each individual tribe and that these visions are used to inform the multiple layers of government and partnerships that would be involved in carrying out each economic vision of the respective tribes. “It’s that connectivity, that everybody is connected and we’re all one of a kind. If we really believe in that and follow that mindset, then all the systems need to be adjusted to support that—including health systems, welfare systems, and financial systems—making it easier to create and maintain businesses, access to home site leases so that we can build and create homes, and adjusting these systems to make them more flexible and leveling the whole playing field,” Lanalle relays. (interview, September 25, 2023)

Ted Piccolo (Colville), senior director of Indigenous Futures at Mission Driven Finance, mentioned that because Native Americans were already late to the financial market decades ago, we are also late to information technology. Now, with easily accessible financial education, we are able to “play catch up, but we are still behind.” He goes on to mention that there are Native CDFIs that are currently incorporating fintech into their financial education and business development trainings, such as Sequoyah Fund, to advance our Native communities. Dr. Christy Finsel (Osage), executive director of the Oklahoma Native Asset Coalition also highlighted the importance of eliminating the digital divide for Native communities. “We are concerned that if everything is put online and the resources are pushed more in our communities, we still have this digital divide: lack of affordable internet services, lack of devices, and lack of training on how to use those devices.” Dr. Finsel is working with Native communities nationally to educate about online services, such as online tax preparation through the Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) program, online banking through the Bank On program, and general online financial education and financial coaching services.

“Solutions to those barriers are for us to continue to provide our voice, our advocacy, and make inroads to these relationships,” declares Chrystel Cornelius (Ojibwe,Oneida), CEO of Oweesta Corporation. “Number one is to fight for our visibility; number two is to promote partnerships; and number three is to really have not only foundations, but private sectors and governments provide us the opportunities that the rest of America enjoys.” The following two articles— “Successes of Grassroots, Native-led Financial Education” and “Prospect for an Economically Thriving Native Nation Seven Generations Out”—analyze indigenous-based solutions to many of the identified barriers to accessing financial education and services.

Wisdom- North/Sage/Conclusion

In conclusion, Native Americans face barriers to accessing mainstream financial institutions, safe, affordable capital, and relevant financial literacy knowledge. Though there are currently efforts to minimize the gaps in physical and digital access, there are many steps to reaching equitable access for all Native community members.

Disclaimer- Mother Earth

There are 574 Federally Recognized tribes and hundreds of unrecognized tribes in the United States, each with a unique colonization story that has influenced their community members’ and descendants’ interactions with the mainstream financial system. These articles are intended to explain a generalized Native experience and support a journey of positive change in relation to Native American, Hawaiian Native, and Alaskan Native communities.

About the Weaver- The Spirit Within

Boozhoo, Migizi ‘ikwe Nindigoo. Stephanie Cote Nindizhinikaaz. Grand Traverse Band Odawa minwaa Ojibwe Nindibendaagoz. Maengun Nidodem.

Hello, spirits know me as Eagle Woman. I am called Stephanie Cote. I am from the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians. I am from the Wolf clan.

Stephanie Cote descends from a lineage of basket weavers. Honoring her ancestry, these articles are woven from common Native knowledge, accessible online articles, and the wisdom imparted by Native peers and elders to support hypotheses developed from the intersectionality of Native American experience and financial education. She is Odawa and Potawatomi from the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians and Grand River Band of Ottawa Indians from Michigan, Certified Professional Coach through the International Coaching Federation, Trauma of Money Certified Professional, and master trainer in several financial education curricula. For more information on Stephanie Cote, please visit www.eaglewomansoars.com.